This is an overview our ArchivesSpace migration process and descriptions of the code used. Hopefully this rather long-winded description helps document our processes and thinking.

Overall, my strategy was to import everything twice. Once we got most of our data into ASpace, I let our staff have a free run of the data to get comfortable with the application. We maintained our previous data stores as masters, and staff could create, edit, and delete ASpace data as much as they wanted. When we were done testing and I was comfortable with all the migration scripts, we cleared out all the data and made a clean import.

Clean-up EAD files for the ArchivesSpace importer

importFix.py

-

Step one was getting all of our EAD data reformatted so they would all easily import into ASpace. I wrote

importFix.pyto make duplicate copies of all of our EAD XML files while stripping out and cleaning any issues that I found would cause errors during import. An example issue was that ASpace didn’t want extent units stored in an attribute like<extent unit="cubic ft.">21</extent>Instead, it wanted<extent>21 cubic ft.</extent> -

We had been using an internal semantic ID system, but we wanted to get rid of these and rely on the ASpace ref_IDs instead, so the script also removes all the @id attributes in

, , etc. -

You can also fix these issues with a plugin that customized how ASpace imports the files. Alex Duryee has spoken on this at SAA and elsewhere. I was already much more comfortable with Python and lxml, so this was faster for a one-off import process.

-

While we had employed a lot of rule-based validation to ensure standardization. There were other issues, like ASpace understood that 1988-03-30/1981-01-01 was an invalid date, but our validation script did not.

-

the script also identified components with empty

<unittitle>tags, etc., so I could get a list of these issues prior to import. Once I had identified the most common problems, this was much easier than having background jobs keep failing halfway through. -

This was a tedious process with lots of trial and error that took almost 2 complete days. I had to re-import a bunch of times, so I wrote

deleteRepoRecords.pyto delete all resource records in ASpace (obviously use cautiously). -

The feedback from ASpace on import issues can be really frustrating. It does not give you feedback on the EAD file that was the culprit, but points you to the new native ASpace record that was never actually created. You have to dig a bit in the log to find the EAD filename. Since I has stripped out our IDs, I was only left with the ASpace ref_id which is not helpful at all in finding individual components among our EAD jungle, so I had to rely on the

<unittitle>and<unitdate>strings. -

You’ll see feedback like, “there’s an issue in note[7].” It takes a while to figure out that note[7] means

<physdesc>, etc. -

We only have one real import incompatibility with ASpace, and that was only one EAD file where 7,800 lines of the 13,000 line file was one gigantic

<chronlist>. ASpace rightly denied this garbage, so we just pulled it out of the finding aid and maybe it will become a part of a web exhibit some day. -

We still had a some messy data when you checked the controlled values lists, but these were few enough that it was easier to identify and clean these issues after the migration.

-

At the end of this process,

importFix.pyallowed us to keep creating and maintaining our EAD files in our current systems, but also let me quickly create ASpace-friendly versions when I need to.

Don’t Repeat Yourself

-

When I wrote the delete resources script I discovered that working with the API is awesome, but I was also repeatedly calling the same API requests. There is no complete Python library for the ArchivesSpace API, so most people make calls manually with requests. Artefactual labs also has a basic library for this, but it doesn’t do a lot for you and still involves manually dealing with a lot of JSON in a way that I didn’t find intuitive. Basically, I wanted to iterate though the ASpace data as easily as lxml loops though XML data. This often involves multiple API calls for a single function.

-

During the course of the migration I started writing a bunch of functions that manage the API behind the scenes. This was I can quickly iterate though collections with

getResources(), collection arrangement withgetTree()andgetChildren()and even find a collection by its identifier withgetResourceID(), or a location by its title string withfindLocations(). Its also handy to have some blank objects at your fingertips, like withmakeArchObj(), so you can create new archival objects without knowing exactly what JSON ASpace needs. -

There’s also some debugging tools I use all time.

pp()pretty prints an object to the console as JSON,fields()lists all the keys in an object, andserializeOutput()writes objects to your filesystem as .json files. -

The library uses easydict to make objects out of the JSON, so you can call it with dot notation (

print collection.title). Writing this library enabled me from rewriting the same code, or finding that script I used last week to steal some lines from. Its really cool to be able to do this:from archives_tools import aspace as AS session = AS.getSession() repo = "2" for collection in AS.getResources(session, repo, "all"): if collection.title = "David Baldus Papers": collection = AS.makeDate(collection, 1964-11, 2001-03) post = AS.postResource(session, repo, collection) print (post) > 200

There are some caveats here. There are a bunch of decisions you make while writing these that I kind of made arbitrarily. It’s probably more complex than it has to be. Ideally, this would be more a a communally-driven effort based on a wider set of needs and perspectives. The code is completely open, so if nothing else, I guess this could provide an example of what a Python library for ASpace might look like. I’m going to try and complete the documentation soon, and if anyone has suggestions I’d really like to hear them. If the community moves to a different approach, I’ll work to update all of our processes to match the consensus, since it will be better than what I can come up with on my own.

Import collection-level records

migrateCollections.py

-

Before ArchivesSpace, we used a custom “CMS” system for collection management and accessioning. We think it’s over 15 years old, and the only way to get data out is directly from the database tables which looked like they were copied from some other system and were overtly complicated and often repeated data. Moreover, the only way to view entire records was to go into edit mode where you could easily overwrite data. If you picked an accession number for a new accession that was already taken, it would just override the old record (!!!). Overall it was a pain to enter information in the system and over time the department slowly stopped updating all but the most necessary fields. Yet, this system had the only total listing of all collections.

-

Over the past year, we found that as we got more and more of our archival description into EAD, we needed an automated way to push this data into our Drupal-driven website, so I pulled a master collection list out of this collection management system, updated and fixed it and just dumped it into a spreadsheet. For each collection it had a normalized name, listed if there was an EAD or HTML finding aid, and had an extent, inclusive date, and abstract for everything not in EAD.

-

While we’ve been making great strides in getting collection-level records for everything, almost 1/3 on our collections sill only had accession records in the old system, and a row in this spreadsheet.

-

This spreadsheet has been our master collection list and a key part of the backend of our public access system (not recommended). ArchivesSpace now allows us to replace this setup by pulling all of this information directly from the API.

-

Yet, with this spreadsheet I could use a Python library for .xslx files to import some basic resource records into ASpace. While they wouldn’t be DACS-compliant, we could still export this basic data to our public access system, and link them to accession records we’ll import later.

-

migrateCollections.pyiterates though the spreadsheet and uses the aspace library to post new resource records in ASpace.

Migrating Accessions

migrateAccessions.py

-

For accessions I asked the Library’s awesome database person Krishna for help. Our old “CMS” was a .asp web application which, from what I can tell, used an old SQL server for its database. I needed something that I could loop though with Python so I asked him to export some CSVs.

-

Once he made the first export we noticed some problems. First there were a lot of commas in some of the fields, so we had to use a different delimiter. The other problem was there was a bunch of carriage returns that use the same character as the csv new line, so we had to escape all these prior to the export. I tried fixing it with a Python script by counting the number of fields in each row and piecing it back together humpty-dumpty-style, but I never want to do something that frustrating again. Luckily with a little time, Krishna was able to escape them before export and use pipes (

|) as the delimiter. -

Once I was able to loop through the table with all the accessions, I met with Jodi and Melissa, some of our other archivists, to identify which fields were still held useful data and how to map them to ASpace accession records. Honestly, we threw out half the data because it was useless, but we were able to reclaim all the accession dates, descriptions, and extents.

-

We had a handful of issues that had to be edited manually. Even though the system returned an error if you forgot to enter an accession number, there were a bunch of records without numbers or records without numbers.

checkAccessions.pyidentified these issues, but we had to go look at each record and try to parse out what happened. The good thing was the data did include a last updated timestamp, which helped a lot. -

Of course the first time I tried this I opened the CSV file in Excel it unhelpfully decided to reformat all of the timestamps and drop all the trailing zeros. Good thing I kept a backup file. Since it was only a handful I ended up doing the edits in a text editor, just to be safe.

-

The cool thing was that the collection IDs were really standardized, so we could easily match them up with the resource records we just created. We just had to convert APAP-312 to apap312, which is a piece of cake with Python’s string methods.

-

The aspace library really came in handy here. Two functions,

makeExtent()andmakeDate()just add extents and dates to any ASpace JSON object. This worked with accessions just as it did with resources. -

The extent was just an uncontrolled string field. Considering this, we had used the field very consistently, but of course there were a bunch of typos or oddly worded unit descriptions. I cleaned up the vast bulk of these issues with Python’s string methods, but there were still some “long-tail” issues that didn’t seem to be worth spending hours on. After all, we haven’t needed real machine-readable accession extents yet, and its not publicly-visible data.

-

For now I just allowed a new extent type “uncontrolled,” and threw the whole field in the number field. We can just fix these one by one as we come across them. I guess I could have dumped the CSV into OpenRefine, but I can also come back later and export a new CSV with the API if we need to clean these up further.

-

After running

migrateAccessions.py, we had accession records and collection descriptions in the same place for the first time. I was really wonderful seeing those Related Accessions and Related Resources links pop up in ASpace.

Locations

migrateLocations.py

exportContainers.py

-

Locations turned out to be the trickiest part of the migration, because our local practices really conflicted with how ASpace manages locations. Theory-wise ASpace does this much better and eventually our practices will improve after the migration, but I had to do some hacky stuff to get ASpace to work with our locations.

-

Basically, in ASpace 1.5+ containers are separated out and managed separately from archival description and connected to both location and description records with URI link. This is great because it lets us describe records independently from how they are managed physically. The newer ASpace versions also let you do some really cool things like calculate extents if you have good data and also supports barcoding.

-

In ASpace collections don’t have locations. How can they, since archival description is really an intangible layer of abstraction that just refers to boxes and folders? In ASpace, collections (or any other description records) are linked to Top Containers (boxes) which are linked to locations. Long-term this is great, since it lets us manage the intellectual content of a collection differently from its physical content.

-

Yet, this poses a very practical problem for us. Our old “CMS” had only one location text field per collection, so we really only have collection-level locations. We’ve never really had a problem with our location records because we have really awesome on-site storage. It also helps that most of our staff has been here a long time, and at least generally knows where most collections are anyway.

-

The location field we had was really messy. This is one extreme real-world example:

H-16-3-1/H-16-2-3,(last shelf has microfilm and CDs with images used for LUNA); G-8-1-1/G-8-2-1; G-17-3-2/G-17-3-1; G-17-4-1/G-17-4-7; G-10-4-1/G-10-4-3; G-10-5-1/G-10-5-8;C-12-2-1/C-12-2-5; C-12-1-2/-12-1-3; SB 17 - o-15 (bound copies of Civil Service Leader digitized by Hudson Micro and returned in 2013, bound and unbound copies of The Public Sector, 1978-1998, digitized and returned in 2015, unbound copies of The Work Force, 1998 through 2012, also digitized); Cold 1-1 - 1-4, E-1-1, A-1-7 - A-1-8, A-1-5 - A-1-7, A-1-9, A-1-8, A-1-8 - A-1-9, A-5-1 - A-5-2, A-5-2 - A-5-3, A-4-9 - A-5-1, A-6-5, A-5-5, A-6-4 - A-6-5 -

So that collection has a bunch of top containers, how do I assign that mess to them? Well this collection in particular is currently being, well, reworked, but for everything else we had to standardize the data into one format, basically:

G-4-2-3/G-4-2-7 (whatever note here); J-3-3-5 (second location here); I-7-3-6 -

Then one of our awesome graduate students, Ben Covell, learned OpenRefine in about a hour and cleaned up all the data in less than a day. (Part of the solution always seems to be having great grad students)

-

Next, we decided it wasn’t worth it to go through every box in the archives to get individual shelf coordinates. Thus, we had two options, either use a separate system for shelf lists, or hack ASpace to make it work.

-

I tried and failed to get ASpace to accept multiple locations per box, which seems like it really shouldn’t be allowed. You can actually have a top container linked to multiple shelves, but it won’t let you then link those boxes to description records.

-

ASpace does let you have previous locations though, but it requires an end date, and the location record to have a temporary label. We decided to have a temporary “collection_level” label and setting the end date to 2999-01-01, and hope that we weren’t creating an insurmountable Y3K problem.

-

Doing it this way meant a lot of work with the API, because we had to find every top container assigned to each collection, translate

G-17-3-8to a ASpace location record, find that record, update that location record to be temporary, and update the top_container record to add each location. This is exactly whatmigrateLocations.pydoes, and with the library it only takes 200 lines of code. -

So that means if a collection-level location was

C-24-2-1/C-24-3-8(16 shelves), every box in that collection (probably about 40-50 boxes) would be linked to each of those 16 locations. -

For larger collections, this would be a bit unwieldy, so the plan is to list individual shelves for larger collections now, and do the rest over time.

exportContainers.pyhelps with this. It makes a .xlsx spreadsheet for each collection that lists every top container and its URI. So we have a directory of spreadsheet files for each collection like apap101.xlsx. We can list the shelf coordinates for each box in that spreadsheet in our same format (K-2-2-3) and use the API to update each top container record over time. Now whenever we’re working with a collection we can fix this problem one by one. -

Finally, ASpace comes with some really cool features like container profiles and shelf profiles, but they’re not mandatory. We decided it wasn’t worth it yet to measure each shelf, but we hope to do this over time in the next couple of years.

-

Overall, migrating locations “the right way” would have taken months and months of effort and involved every staff member in the department. Instead, I was able to basically do it myself with a little help in about a week. We might run into a problem if updates to ASpace changes how the application handles these records, but even in that worst-case scenario we can just export all our incompatible locations with the API before upgrading and use a separate shelf list system. Our data will even be a lot better too.

Learn by Breaking Things

-

We really didn’t have the option to bring in Lyrasis to do workshops for our staff on how to use ASpace. This is going to be the primary medium for our department to create metadata and make our holdings available, so they need to be comfortable with it, and switching everyone over to a whole new system without any formal prep is a lot to ask.

-

The best way I find to learn a tool is to get some hands-on experience and try and break it to see where the boundaries are. Migrating all our data twice, not only lowered the stakes for the first import, but it gave us a lot of time with a fully-running ArchivesSpace with a lot of realistic test data. I opened it up to the our department and encouraged them to make new resources and accessions, delete things, and generally try test their boundaries and get comfortable. I pointed them to some guides shared by the SAA Collection Management Tools Section, and they also said there’s a bunch of screencasts on YouTube that really helped.

-

Overall, ASpace is very intuitive, and easy to use if you comfortable working with web applications. Our department has taken to it fairly quickly, and I don’t think more formal training would of helped much. Having a really good sandbox and dedicating real time to experimenting with it is definitely key.

-

We’re also still working on establishing best practices for use and documentation for our students. I think this is actually a bigger hurdle than leaning the tool itself.

Building Satellite Tools

-

The best reason for implementing ArchivesSpace isn’t necessarily its basic functionally of creating and managing archival description. ASpace’s open architecture means that essentially all the data in the system can be read or updated with the API. This is not only for automating changes, but it also allows us to use other tools to interact with our data.

-

The other really cool thing is that the ASpace API is backed by a data model. This way it closely defines its acceptable data, and rejects anything outside of its parameters. I’ve found that this is makes life so much easier than say, managing your data in XML, since it has the effect of making your data much more stable.

-

If ASpace doesn’t do something the way you like, you can just use a different tool to interact with your ASpace data. This way, ASpace can really support workflows that embrace the separation-of-concerns principle. Here ASpace is at the center of an open archives ecosystem, and you can have smaller, impermanent tools to fill specific functions really well. Often, a modular system like this can be easier to maintain, as in the future you can replace these smaller tools one-by-one as they become obsolete, rather than the daunting task of one huge migration.

-

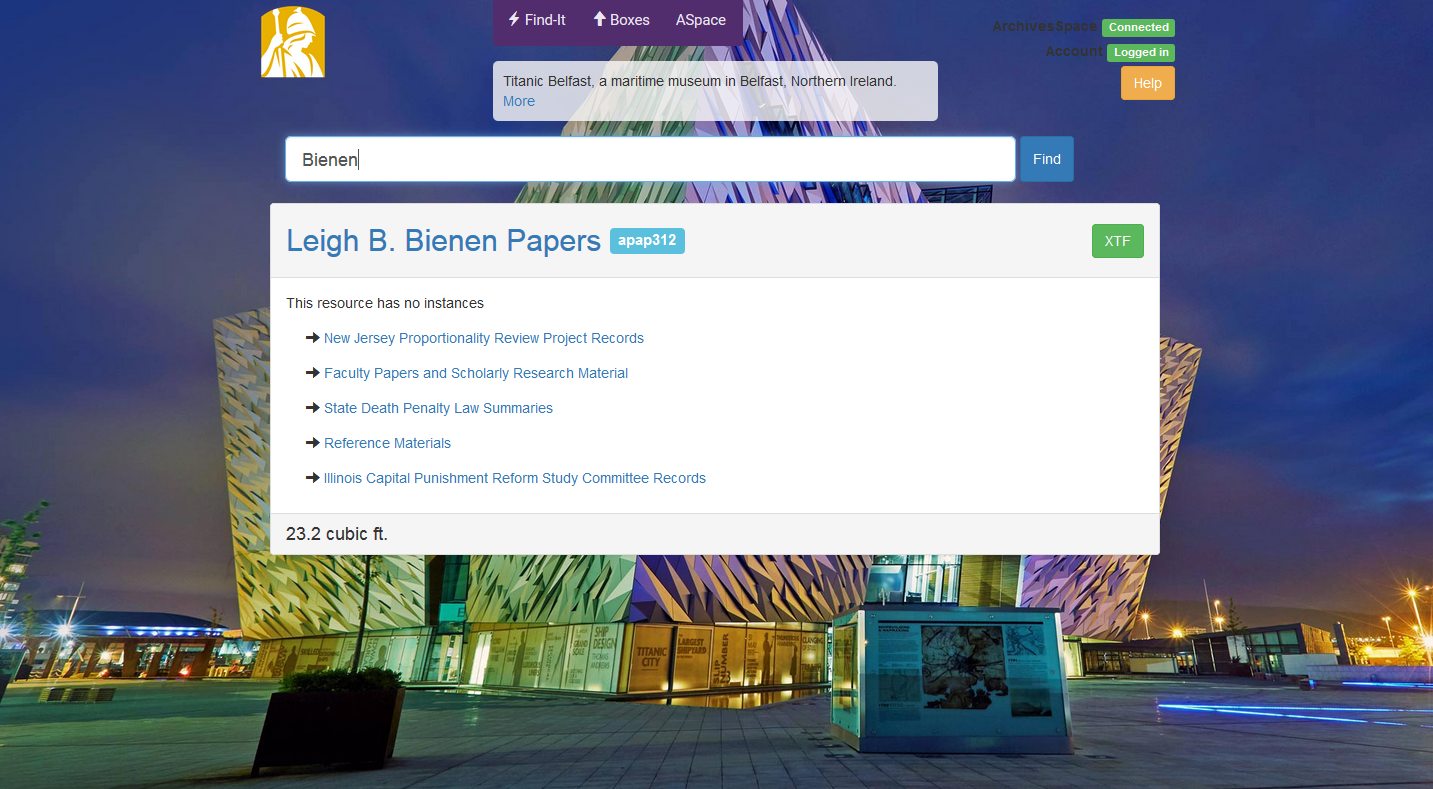

A lot of this is built upon the work Hillel Arnold and Patrick Galligan have done at the Rockefeller Archive Center. They wrote a plugin that lets you work with the API from a single HTML page with JavaScript. They used this to write Find-it, a simple text field to return locations for ASpace ref_ids.

-

Find-It solved a key problem for us as one of the only things our old “CMS” did really well was that you could type in “Crone” and quickly get shelf locations for the Michelle Crone Papers. Our other archivists were asking for something similar in ArchivesSpace, and didn’t like they you had to look through three different records to get this information in ASpace. Yet, the odd way I did our locations posed some problems. Ref_ids would also work, but we needed to return locations for top containers assigned to resources as well.

-

With my hacky JavaScript skills (and some help from Slack) I set it up to also return locations for resources using the search API endpoint and the id_0 field. Using the search API made me realize that I could also make an API call that returns a keyword search for resources. The search returns links to the Resource page in ASpace and XTF as well, which makes Find-it a really quick first access point to our collections as well.

-

The last request I got was for some way to access locations from resources with lower levels of description, so I was even able to call the resource tree and add links to lower levels if there are no instances. I just made find-it accept ids as a hash and these links just reloads the page with that lower-level ref_id. Overall it became a bit more complex than I was envisioning. Our fork is here, but I’d recommend starting with Rockefeller’s much cleaner version and using ours as more of an example.

-

Finally, the single search bar on a white background was really boring, so I wrote a quick script that updates the background to Bing’s image of the day API.

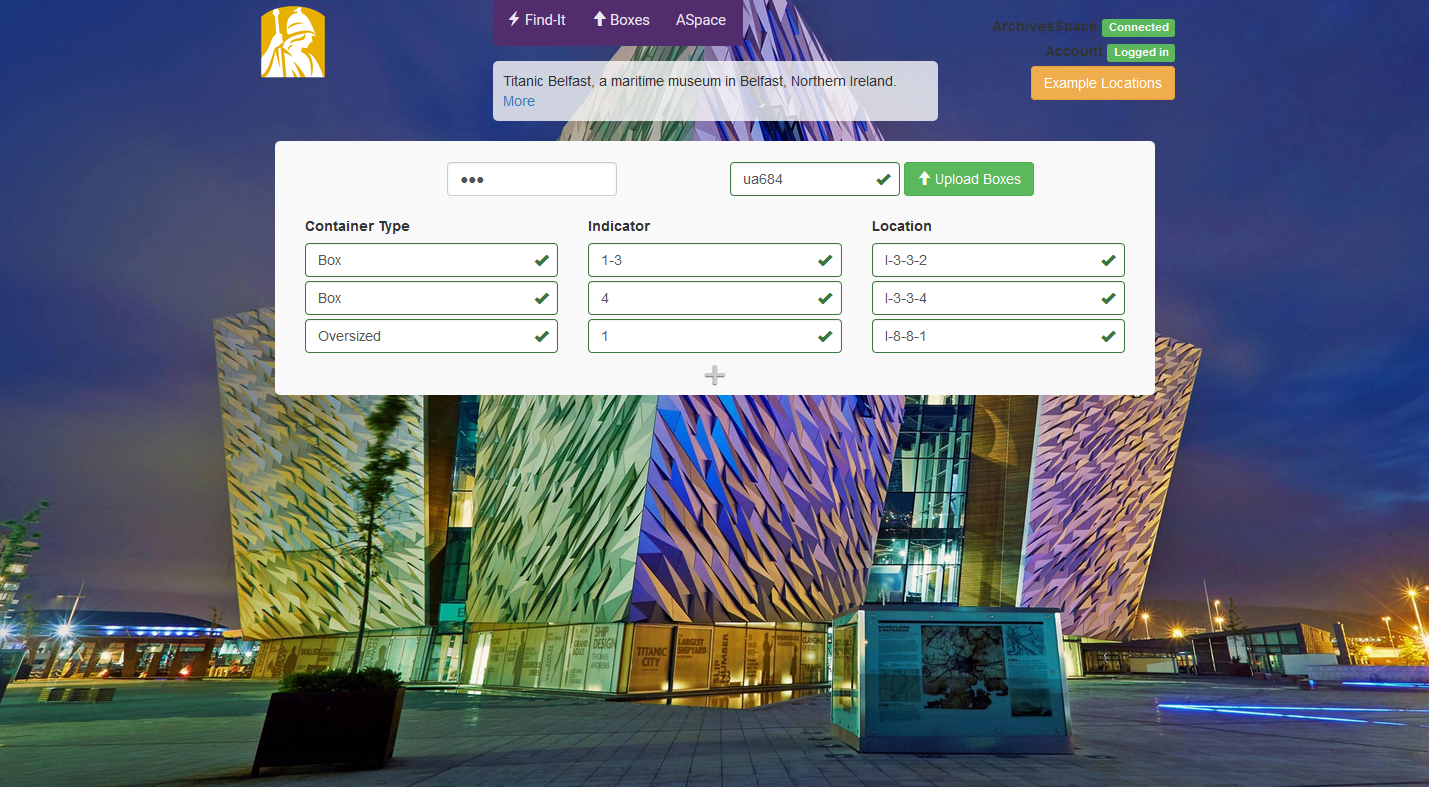

- Another workflow issue we found was how tedious it could be to enter in individual containers for large accessions. Say we got a new collection of 50 boxes. ASpace makes you create each of these boxes, which is good, but very tedious. So I basically used the same framework as Find-it, figure our how to get ASpace to accept Cross-Origin post requests, and made a single-page box uploader. Now we can just list new boxes in these fields with our old-style shelf coordinates, and a bunch of JavaScript will create and assign all these new top containers to a resource.

-

The last request I got from out staff was for creating container list inventories. We use undergraduate student assistants to do most of this data entry work, and we found that ASpace rapid data entry would require a good amount of training for our students who work few hours with a really high turnover rate.

-

So I wrote some Python scripts to manage inventory listings with spreadsheets and the ASpace API. One parses a .xslx file and uploads file-level archival objects through the API. It will also take a bunch of access files and makes digital objects, places the files on our server and links them to archival objects. Another script reads an existing inventory back to a spreadsheet with all the relevant URIs so we can roundtrip these inventories for future updates.

-

I also envision this as a near-term solution, as its possible that we end up doing all this natively in ASpace in the future. The cool thing is that the ASpace API makes all these tools really easy and quick to make, and they solve real immediate problems for us. Yet, none of these tools are really essential for us, and if they become too difficult to manage, we can just drop them and move on to something else.

Migration Day(s)

EAD import

importFix.py

checkEAD.py

-

When migration day came, we dumped the database, deleted the index, and started from scratch. I had Krishna export new CSVs from our old system with any updated records that were made since the previous export. By this point the plan was that migration scripts were done and tested and everything would go relatively seamlessly. I was hoping to get everything imported in a day or so, and minimize the downtime when staff were not allowed to make updates.

-

When it came time for the EAD import, some recent EADs/updated had happened, and I still got 2 minor errors for about 630 EADs, so I didn’t actually get the Holy Grail of a perfect EAD import.

1963-0923and1904-01/1903-07are not valid dates and ArchivesSpace, but these were easy fixes. -

One thing I had noticed during the first time was than when you import a large amount of EADs, it takes the index awhile to catch up. ASpace still told me I had only 465 resources instead of 633, but that soon updated to 503. Yet, in about an hour I was still missing 29 collections. I assumed that this was still the index, but I quickly wrote checkEAD.py to see how many collections I could access though the API and I was still missing 29.

-

It turned out that two import jobs had actually failed, but ASpace listed them as Complete for some reason. One issue was when we changed an ID and there was an eadid conflict, and the other issue was that I totally forgot about that huge

<chronlist>that failed the first time. -

These were easy fixes but the lesson here is always test your imports and don’t trust the index.

-

The importing ended up taking most of the afternoon, so I discovered my one-day migration plan was over-optimistic.

Clean Resource Identifiers

fixNam.py

- For collection identifiers we had been unsing the prefix

nam_which is our OCLC repository ID or something, but we decided that this was overtly complex and not useful, so we decided to drop these late in the migration planning. While theimportFix.pyscript was written to clear thenam_prefix from the<ead> @idand<eadid>, but I forgot to do this to the collection-level<unitid>. Unfortunately I found out the hard way that this is what ASpace ends up using as theid_0, so I whipped upfixNam.pyto strip this post-import rather than start the process over again.

Collection-level spreadsheet import

migrateCollections.py

-

Importing the basic collection-level records from the spreadsheet went fairly well. I realized that we also needed a normalized name for each collection in the resource records somewhere. For example, the “Office of Career and Professional Development Records” needed to be accessible somewhere as “Career and Professional Development, Office of; Records” so it would be alphabetized correctly in our front end. So, I added a few lines in

migrateCollections.pythat adds these normal names in the Finding Aid title field. -

One annoying thing was that after I posted all the spreadsheet records, the index was a bit slow to update. I was all set to migrate the accessions, but to match them up with the resource records, I had to use the index to search for matching id_0 fields. However, within an hour or so suddenly ASpace had updated the index, and I was all set.

-

ASpace told me I had 904 resources, which was curiously two more than we had in our master list. I assumed we failed to update our master list for two EADs and I imported them from the spreadsheet as well.

-

To confirm all the collections, I wrote

checkCollections.pyto see what was up. It turned out that when we had updated that ID we still had a duplicate EAD file floating around, and another recent collection had an EAD file but was never entered in to the spreadsheet. These issues were easily fixed and all our collections were done.

Accessions and Locations

migrateAccesions.py

checkAccessions.py

migrateLocations.py

checkLocations.py

-

The accessions and locations went easy without any issues. This time I wrote

checkAccessions.pyto find all the accession issues from last time around, and everything went nicely. -

Some of the locations had been updated since the last import, so

checkLocations.pyverifies that these locations are indeed in ArchivesSpace, prior to running the import scripts.

Export Scripts

exportPublicData.py

lastExport.txt

exportConverter.py

staticPages.py

-

Once we had migrated all of our data into ArchivesSpace, it was time to set up scheduled exports and connect everything with our public access system that consists of XTF and a sets of static pages.

-

Rockefeller’s asExportIncremental.py is a good source for how to do export EADs from ASpace incrementally. I followed the same basic idea, but omitted the MODS exports, and simplified it a bit into

exportPublicData.py. I integrated the same API call into the aspace library asgetResourcesSince()which takes a POSIX timestamp. Instead of using Pickle I just wrote the last export time to a text file calledlastExport.txt. -

ASpace’s EAD exports didn’t exactly match up with what we had been using in XTF. You can change these exports with a plugin, but I found it easier to both make some changes in our XTF XSLT files, and write a quick

exportConverter.pyscript with lxml. -

exportPublicData.pyloops though all the resources modified since the last export and only exports records that are published. Since we still have a bunch of resources that only have really simple collection-level descriptions, I didn’t want to export EADs and PDFs for these, so I just exported the important information to a pipe delimited CSV. -

I has always envisioned the ASpace API as completely replacing our spreadsheet that generates the static browse pages for our public access system. Yet, I didn’t want to export all that data over and over again, only make incremental updates like the EAD exports. Since my original static pages scripts were designed to loop though a spreadsheet, shifting to CSVs wasn’t very difficult. I also didn’t want to spend a lot of time changing things since we have some longer-term plans to export this data into a web framework.

-

exportPublicData.pyupdates this CSV data for modified collections as it exports EAD XML files. It then uses Python’s subprocess module to call git commands and version these exports and pushes them to Github. It then copies new EAD files to our public XTF instance. Finally, it callsstaticPages.pyto create all of the static browse pages. -

I had some encoding errors that were a pain to fix, so I ended up writing these scripts for only Python 3+.

-

These scripts are set up to run nightly, a few hours before XTF re-indexes. The result is that staff can make changes in ASpace, create new collections or subjects, and the new public access system pages will appear overnight, without any manual processes.

Timelines

-

So, how long did this all take? We got ArchivesSpace up an running on a server near the end of December 2016, really started the migration scripts during the start of February, and finished up everything on the second week of April. Most of the migration prep time spent was in February and the first week of March, and most of March was devoted to staff testing/experimenting and writing the smaller workflow tools.

-

The final migration ended up taking about 2 1/2 workdays, which I’m fairly happy with. That was the only downtime we had when changes couldn’t be made.

-

This was also not committing a large department-wide effort. It was mostly me managing everything, and although it was probably my primary project during that period, I was also managing the regular day to day tasks of the University Archives: doing accessions and reference, managing students, and working with other offices on campus to transfer their permanent records, and also service and (not very much) scholarship. I’m also lucky to have two excellent graduate students in the University Archives this year, Ben Covell and Erik Stolarski. It really can’t be understated how having really bright and hardworking students enables us to do so much.

-

This timeframe is also a bit deceiving, as the real work started about 2 years ago when we worked to really standardize our descriptive data. A lot of the work we did back then really shortened up our timeline, as we didn’t have to do wholesale metadata cleanup before migrating. Our data still has some issues though, but ArchivesSpace has some features like the controlled values lists that can help fix some of our irregularities after migrating. The cool thing about this is that a lot of the clean up work can be distributed, as anyone in the department can easily make fixes whenever they see something.

-

Additionally, we cut some corners on the data-side – particularly the locations. There are some long-term costs here as I decided to take lot of the labor required to straighten out all this data, and spread it out over time. I’m happy with this decision, as we have other competing priorities, like getting good collection-level records for everything, and overall increasing access to collections. We also could have put off the migration until some of our problems could be fixed, but there were significant maintenance costs to our old way of doing things that we really don’t have anymore. I’m hoping this frees us up to work on some of the more ambitious project we have planned.

Author

Greg Wiedeman